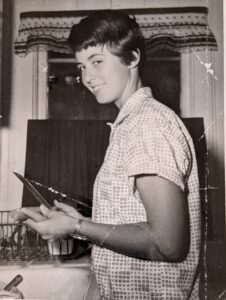

Amonda Marie Jones, 1940-2025

On November 3, 2000, my mother closed on the sale of her townhouse in Loveland, Colorado.

“I’ve always wanted to live in a big city, New York or San Francisco,” she had told me, announcing her plan to move. “If I don’t do it now, I never will.”

The date of the real estate closing coincided with her sixtieth birthday.

She headed east two months later. Her little black Dodge Neon, stuffed with enough essentials to launch her new venture, was aimed toward Brooklyn, where the youngest of my three older brothers lived. He’d attended Columbia University in the early 80s and never left New York. He made a few introductions, and in short order Mom had found a one-bedroom apartment about a mile and a half from where he lived in Williamsburg and was negotiating with a family in Manhattan that was looking for a housekeeper/nanny.

She started becoming a New Yorker by mapping her local precincts on foot. Unlike the simple grid of streets and avenues that covers most of Manhattan, the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn is a jumble. The area encompasses multiple historic towns that were platted on different orientations, creating a patchwork of neighborhoods with streets running on, and meeting at, wonky angles. The sweeping ramps serving the Williamsburg Bridge and the elevated tracks of the JMZ subway lines overlie the muddle, while the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway cuts through it all with a multi-lane slither and incessant roar. The human inhabitants are, if anything, an even wilder mashup. A more extreme contrast from the small-town homogeneity of Loveland would be hard to find within the continental US.

Mom settled into her routines within the chaos, bargain-hunting in the cramped grocery stores, schlepping her beer home from the closest bodega, commuting to Manhattan on the L-line. At work on the Upper West Side, she learned the ropes of high-rise New York, albeit from a working class perspective.

She was an anomaly: a white-haired white lady in a job most often filled by immigrants or women of color. I tagged along once or twice while visiting, alternately amused and in awe of the streetwise mien she adopted in the city. Her walk matched the hustling pace of a stockbroker late for a meeting. She snapped at interlopers who bumped into her, kept her wallet hidden, held her own in the gladiatorial queues of the Zabar’s deli. One jeans pocket was reserved for quarters and one-dollar bills, which she doled out to a handful of street people she’d come to know by name. One of her duties was passing on her newly-honed street smarts to her employer’s daughter, an over-protected teen who had grown up in Manhattan but had never learned to navigate on a bus or the subway.

She hadn’t left for work yet on September 11, 2001, when the planes hit the World Trade Center. My brother and brother-in-law were on vacation in Europe, their return flight delayed for almost a week. In the aftermath of the towers’ fall, when a collective spirit permeated the city more thoroughly than the dust and smoke, Mom’s fealty to her adopted home town was cemented.

***

She had already made plans to fetch the rest of her belongings and furniture in Colorado that fall, and in late October we loaded up a rental truck and set out on the cross-country trip together. Engine noise permeated the cab, and every panel, bolt, window, and seat frame rattled incessantly. The radio only added to the din and we had to yell to converse, so mostly we didn’t. When I wasn’t driving (and sometimes when I was), I made a game of counting red tailed hawks perched on power poles along the interstate.

There was never any question that Mom would drive the final leg, from New Jersey into Brooklyn. The tunnels into Manhattan were still closed to trucks, so we roared across Staten Island and the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and then along the western edge of the vast sprawl that is Brooklyn on I-278, aka the BQE. We had waited until late evening to tackle the crush of urban driving. Traffic was light enough to be moving at freeway speeds, which only made the ride more terrifying. The lights of the altered Manhattan skyline must have risen in front of us and then shifted to our left as we traveled north, our surroundings lit by amber streetlights and the autumn dusk, but I don’t remember much other than the noise and Mom, leaned toward the wheel, checking her mirrors in rapid-fire sequence, gunning the truck toward her little apartment on Lorimer Street.

It’s in that passage, perhaps—the motor’s high-pitched grinding, the jarring crash of potholes, the crappy pavement chattering the cab’s hard surfaces, the enveloping crush of aggressive New York driving—that the mini-story I’d tell for years about my mother took shape. On her sixtieth birthday, I would say, my mom left the life she’d known, packing up and heading to The City. “I hope I’m that ballsy when I’m that age,” was the inevitable concluding line.

I don’t know how many times I delivered that punchline over the next couple of decades, but I repeated the story whenever I was in a position to explain why my mother lived in New York and not Colorado. When I turned sixty myself in April this year, I realized I’m going to have to update my script. The question implied by the line has been answered. Will I be that ballsy at the age my Mom was then? No. Not even close.

***

New Year’s Eve 2009, in NY, gussied up for one of the notorious New Year’s Eve parties hosted by my brother Doug and brother-in-law Koitz. Photo credit Koitz.

While Mom went urban, I went wild. Her move to NYC roughly paralleled my own migration from Boulder to rural central Colorado. Doug and I had bought this property, part of a subdivided ranch, in 1995, and in the spring of 2001 we began the years-long process of establishing a home here. We built a barn with an attached cabin, living there while the house was under construction. We set up a walled garden, fenced pastures, got horses. Doug sold wine, I wrote and indexed books from home.

Mom, meanwhile, got doormen, building superintendents, and my brother’s friends hooked on her homemade cookies, banana bread, and deviled eggs. She picked up freelance seamstress gigs and hoarded her beer cans for the elderly Haitian woman who made late-night rounds collecting recyclables in a rattling shopping cart. She took in museums and attractions, exploring the city’s boroughs via public transportation, in her car, and at times on foot, saving the maps and guides she collected during her peregrinations in a decorative tin on the end table next to the couch. Always a news hound, she luxuriated in taking the New York Times as her daily hometown newspaper.

A few years after settling in the city, she found a place, as they say, “upstate.” The proceeds from her Loveland townhouse bought her a very old and slightly decrepit little house on the west bank of the Hudson River in a town called Coxsackie. She finally stopped working in her late 70s, spending her time puttering in the yard and on unceasing projects around the house. She adored the river and its traffic of barges and boats, although it was a difficult love, given that the Hudson in flood stage would wind up in her basement. She sold the house in 2020 and moved back to Brooklyn full time. She and her part-time roommate shared the first floor apartment below my brother’s place.

***

As much as I’d love to report that Mom lived out her days as a New Yorker, she took an abrupt skid into vascular dementia in January, 2024. When caring for her at home became too much for me and my brothers, we decided to move her back to Colorado, near me. She was philosophical on the late September morning when I broke it to her that she had to leave. She obliged as we packed, climbed into the Uber, sat calmly in the wheelchair as we navigated the terminal at Laguardia. On the plane, she stole my brother’s beer, but was otherwise stoic. As we were driving south from the airport, though, bound for a memory care facility in Colorado Springs, she broke down in sobs.

Mom died on February 21, 2025. There are many, many things about the last fourteen months of her life I wish were different. We were all helpless in the face of her psychosis and cognitive decline, but denying her the opportunity to die in the home place she had chosen for herself haunts me. Perhaps I’m projecting my own attachments onto her. I know what it feels like to find your place, an environment that gives you the sense that you can be the person you were meant to be. At sixty, I’ve had the unbelievable good fortune of having lived in that place for almost twenty-five years. Mom, at the age I am now, was still searching.

My mother was born in Pueblo, Colorado but mostly grew up in Chico, California. She regularly visited an aunt who lived in Pueblo, and that’s where she met and fell for my dad. She was eighteen and pregnant when they married on New Year’s Eve, 1958. All four of us kids were also born in Pueblo, in the span of six years. Dad divorced Mom in 1978, a couple of years after she’d left him, and us. My theory for her departure is that she had come to regard herself as too damaged to live in the same house with us without hurting someone. She worked hard to stay present in our lives in various ways; she went to New York, in part, to be near my brother. But the fracture that ran through our growing-up has mostly made itself known through silence.

My mother was an introvert and a loner and it feels right to say she buried her emotions under hard work whenever she could. She was opinionated and honest, with a cutting wit and a sharp tongue that she increasingly kept sheathed as she grew older. It’s not possible to capture the scope of a person in a few words. But as I seek to memorialize Mom without soft-pedaling her stubborn reclusiveness, that quarter-century in New York shines in my mind. It occurs that she most loved the city for its quintessential characteristic: despite its density, noise, and diversity—or perhaps because of those qualities—it preserves solitude for the individuals who crave it, even as it opens spaces, however narrow, for them to insert themselves in the human flow, and ebb.

That brought tears to my eyes several times, Andrea. It’s so well-written that feel a bit as though I’d known her, and I realize something of what I missed in NOT knowing her. Thank you so much for that fine essay, and I strongly urge you to put it into your next book.

Dear Linda, thank you so much. This all means a lot coming from you, my mentor. You two would have found plenty to talk about. This piece might not fit in the next book, as I am still working on that science project, but here’s hoping for the one after that.

Dear Annie, This is such a beautiful piece you wrote…such an honor for your Mom….your love and awe of her is palpable. Each sentence and photo speaks so much. What a journey to get to know her and thus yourself, from the perspective of being ‘grown up’. While reading, I caught many glimpses of memories of you and her, and of my own journey with my Mom, and what my daughter may someday feel & realize as she navigates my old age. Wow, 60! We just turned 60. What an amazing gutsy woman to live out loud on her terms! Such an inspiration! Thank you, Annie for sharing your beautiful story. Hugs and love, Ann

Sweet Ann, thank you. Isn’t 60 a weird milestone?? The journey continues. I’m thinking of you and your family. We find the moments to prize within the baffling flow. Sending hugs and love back to you.

Glad she had that time in New York – I think you nailed it about the solitude that’s possible while being able to choose the depth of connection that you want in a big city. And it sounds like she had family that were always ready to help and to do what’s most needed, even when it must have hurt a lot.

Thank you for reading, Michael. I think most families have their complicated aspects. Mom was an original, and I’m lucky to have had her in my life for so long.

A lovely piece to memorialize your mother, a complex and fascinating person, by these accounts. And how good to see you here again, after all this time.

Pat, I appreciate your kind words. Mom was wonderful and difficult–a description I aspire to! I keep trying to re-establish my writing rhythm here. Composing something about Mom, who filled so much of my time over the past year plus, felt like it needed to be done. Perhaps now the stopper has been pulled out.